Cocoa’s child

laborersMars, Nestlé and Hershey pledged nearly two decades ago to stop using cocoa harvested by children. Yet much of the chocolate you buy still starts with child labor.

June 5, 2019

Thank you to the journalists and the Washington Post for publishing this article, on a topic our circle has long discussed through the #chocolatefreedomproject I started! Read the article at this link:

Or scroll down below my photo to read the full article right here.

Your friend in slavery-free chocolate,

Valerie

Valerie Beck

Founder, Chocolate Uplift

*****

Cocoa’s child laborers

Mars, Nestlé and Hershey pledged nearly two decades ago to stop using cocoa harvested by children. Yet much of the chocolate you buy still starts with child labor.

Behind much of the world’s chocolate is the work of thousands of impoverished children on West African cocoa farms.

GUIGLO, Ivory Coast — Five boys are swinging machetes on a cocoa farm, slowly advancing against a wall of brush. Their expressions are deadpan, almost vacant, and they rarely talk. The only sounds in the still air are the whoosh of blades slicing through tall grass and metallic pings when they hit something harder.

Each of the boys crossed the border months or years ago from the impoverished West African nation of Burkina Faso, taking a bus away from home and parents to Ivory Coast, where hundreds of thousands of small farms have been carved out of the forest.

These farms form the world’s most important source of cocoa and are the setting for an epidemic of child labor that the world’s largest chocolate companies promised to eradicate nearly 20 years ago.

500 MILES

e

r

g

i

N

Detail

SENEGAL

MALI

NIGER

BURKINA

GUINEA

FASO

S. LEONE

NIGERIA

BENIN

IVORY

CHAD

TOGO

COAST

Guiglo

L

GHANA

I

B

E

R

Yamoussoukro

I

A

Lagos

Abidjan

CAMEROON

“How old are you?” a Washington Post reporter asks one of the older-looking boys.

“Nineteen,” Abou Traore says in a hushed voice. Under Ivory Coast’s labor laws, that would make him legal. But as he talks, he casts nervous glances at the farmer who is overseeing his work from several steps away. When the farmer is distracted, Abou crouches and with his finger, writes a different answer in the gray sand: 15.

Then, to make sure he is understood, he also flashes 15 with his hands. He says, eventually, that he’s been working the cocoa farms in Ivory Coast since he was 10. The other four boys say they are young, too — one says he is 15, two are 14 and another, 13.

Abou says his back hurts, and he’s hungry.

“I came here to go to school,” Abou says. “I haven’t been to school for five years now.”

Children from impoverished Burkina Faso take a break from work on a cocoa farm near Bonon, Ivory Coast.

A worker cuts a cocoa pod to collect the beans.

A steady stream of buses from Burkina Faso carry passengers and trafficked children as young as 12 to work in cocoa fields in Ivory Coast.

‘Too little, too late’

The world’s chocolate companies have missed deadlines to uproot child labor from their cocoa supply chains in 2005, 2008 and 2010. Next year, they face another target date and, industry officials indicate, they probably will miss that, too.

As a result, the odds are substantial that a chocolate bar bought in the United States is the product of child labor.

About two-thirds of the world’s cocoa supply comes from West Africa where, according to a 2015 U.S. Labor Department report, more than 2 million children were engaged in dangerous labor in cocoa-growing regions.

When asked this spring, representatives of some of the biggest and best-known brands — Hershey, Mars and Nestlé — could not guarantee that any of their chocolates were produced without child labor.

“I’m not going to make those claims,” an executive at one of the large chocolate companies said.

One reason is that nearly 20 years after pledging to eradicate child labor, chocolate companies still cannot identify the farms where all their cocoa comes from, let alone whether child labor was used in producing it. Mars, maker of M&M’s and Milky Way, can trace only 24 percent of its cocoa back to farms; Hershey, the maker of Kisses and Reese’s, less than half; Nestlé can trace 49 percent of its global cocoa supply to farms.

A worker stands on dried cocoa beans outside an Ivory Coast cooperative facility. About two-thirds of the world’s cocoa supply comes from West Africa.

Workers gather dried cocoa beans outside an Ivory Coast cooperative facility.

Men unload bags of cocoa near the office of Cargill, one of the leading cocoa suppliers for the chocolate industry.

With the growth of the global economy, Americans have become accustomed to reports of worker and environmental exploitation in faraway places. But in few industries, experts say, is the evidence of objectionable practices so clear, the industry’s pledges to reform so ambitious and the breaching of those promises so obvious.

Industry promises began in 2001 when, under pressure from the U.S. Congress, chiefs of some of the biggest chocolate companies signed a pledge to eradicate “the worst forms of child labor” from their West African cocoa suppliers. It was a project companies agreed to complete in four years.

To succeed, the companies would have to overcome the powerful economic forces that draw children into hard labor in one of the world’s poorest places. And they would have to develop a certification system to assure consumers that a bag of M&M’s or a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup did not originate with the swinging of a machete by a boy like Abou.

“I admit that it is a kind of slavery. … But they bring them here to work, and it’s the boss who takes the money.”

Ivory Coast farmer

Since then, however, the chocolate industry also has scaled back its ambitions. While the original promise called for the eradication of child labor in West African cocoa fields and set a deadline for 2005, next year’s goal calls only for its reduction by 70 percent.

Timothy S. McCoy, a vice president of the World Cocoa Foundation, a Washington-based trade group, said that when the industry signed onto the 2001 agreement, “the real magnitude of child labor in the cocoa supply chain and how to address the phenomenon were poorly understood.”

Industry officials emphasized that, according to the pledge made to lawmakers, West African governments and labor organizations also bear some responsibility for the eradication of child labor.

Today, McCoy said, the companies “have made major strides,” including building schools, supporting agricultural cooperatives and advising farmers on better production methods.

In statements, some of the world’s biggest chocolate companies that signed the agreement — Hershey, Mars and Nestlé — said they had taken steps to reduce their reliance on child labor.

Other companies that were not signatories, such as Mondelez and Godiva, also have taken such steps, but likewise would not guarantee that any of their products were free of child labor.

In all, the industry, which collects an estimated $103 billion in sales annually, has spent more than $150 million over 18 years to address the issue.

But when the businesses initially made the promise to eradicate child labor, according to industry insiders and documents, the companies had little idea of how to do so. Their subsequent efforts have been stalled by indecision and insufficient financial commitment, according to industry critics.

Their most prominent effort — buying cocoa that has been “certified” for ethical business practices by third-party groups such as Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance, has been weakened by a lack of rigorous enforcement of child labor rules. Typically, the third-party inspectors are required to visit fewer than 10 percent of cocoa farms.

“The companies have always done just enough so that if there were any media attention, they could say, ‘Hey guys, this is what we’re doing,’ ” said Antonie Fountain, managing director of the Voice Network, an umbrella group seeking to end child labor in the cocoa industry. “It’s always been too little, too late. It still is.”

“We haven’t eradicated child labor because no one has been forced to,” Fountain added. “What has been the consequence . . . for not meeting the goals? How many fines did they face? How many prison sentences? None. There has been zero consequence.”

According to the U.S. Labor Department, a majority of the 2 million child laborers in the cocoa industry are living on their parents’ farms, doing the type of dangerous work — swinging machetes, carrying heavy loads, spraying pesticides — that international authorities consider the “worst forms of child labor.”

A smaller number, those trafficked from nearby countries, find themselves in the most dire situations.

During a March trip through Ivory Coast’s cocoa-growing areas, journalists from The Washington Post spoke with 12 children who said they had come, unaccompanied by parents, from Burkina Faso to work on cocoa farms.

While the ages they gave were consistent with their appearance, The Post could not verify their birth dates. In much of Burkina Faso, as many as 40 percent of births go unrecorded in official records, and many children lack identification documents.

The farms were easily visited because they typically lack fences, but people were often reluctant to talk about child labor, which is known to be illegal and is officially discouraged.

Asked about the extent of child migrants working on Ivorian cocoa farms, the farmer overseeing Abou and the other boys noted the steady stream of buses carrying people from Burkina Faso into the area. The Post’s reporters also observed those buses during the March visit.

There’s “a lot of them coming,” said the farmer, who asked that his name not be used because he didn’t want to attract attention from the authorities. “It’s them who do the work.”

The farmer said he was paying the boy’s “gran patron,” the “big boss” who manages the boys, a little less than $9 per child for a week of work and who would, in turn, pay each of the boys about half of that.

The farmer said he considers the boys’ treatment unfair but hired them because he needed the help. The low price for cocoa makes life difficult for everyone, he said.

“I admit that it is a kind of slavery,” the farmer said. “They are still kids and they have the right to be educated today. But they bring them here to work, and it’s the boss who takes the money.”

A young boy from Burkina Faso follows other children as they leave the cocoa farm where they work.

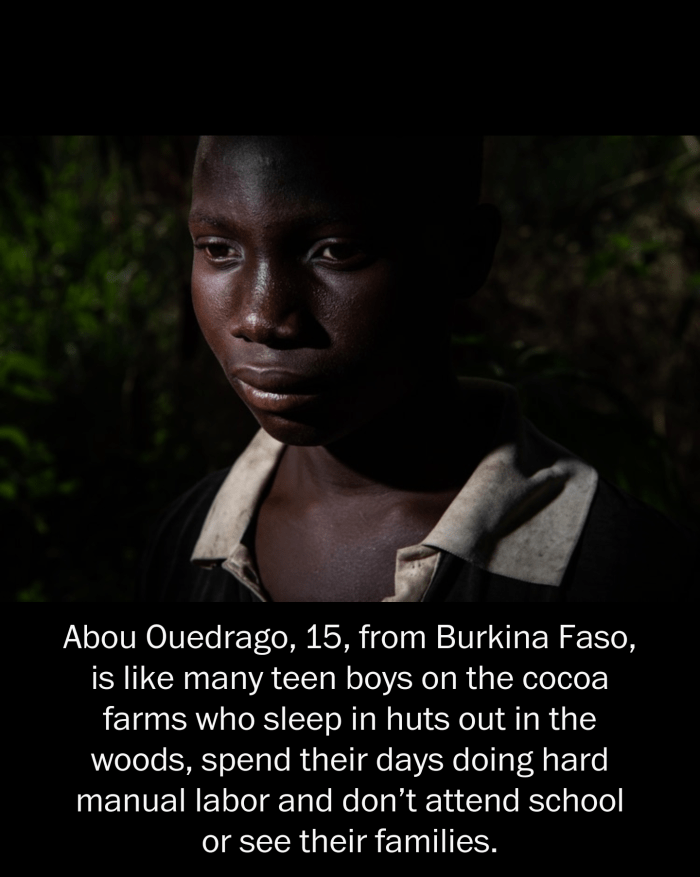

Abou Ouedrago, 15, from Burkina Faso, is like many teen boys on the cocoa farms who sleep in huts out in the woods, spend their days doing hard manual labor and don’t attend school or see their families.

Abou Ouedrago uses a machete to chop down a tree on a cocoa farm.

Children on a break from work at a cocoa farm share white-colored water that was scooped into a bucket from a nearby pond.

A young boy from Burkina Faso rests on the ground during a break from work on a cocoa farm.

‘It happens on a large scale’

What makes the eradication of child labor such a daunting task is that, by most accounts, its roots lie in poverty.

The typical Ivorian cocoa farm is small — less than 10 acres — and the farmer’s annual household income stands at about $1,900, according to research for Fairtrade, one of the groups that issues a label that is supposed to ensure ethical business methods. That amount is well below levels the World Bank defines as poverty for a typical family. About 60 percent of the country’s rural population lacks access to electricity, and, according to UNESCO, the literacy rate of the Ivory Coast reaches about 44 percent.

With such low wages, Ivorian parents often can’t afford the costs of sending their children to school — and they use them on the farm instead.

Other laborers come from the steady stream of child migrants who are brought to Ivory Coast by people other than their parents. At least 16,000 children, and perhaps many more, are forced to work on West African cocoa farms by people other than their parents, according to estimates from a 2018 survey led by a Tulane University researcher.

An aerial view of Duakoua, a city in the heart of Ivory Coast’s cocoa region.

“There is evidence that it happens, and it happens on a large scale,” said Elke de Buhr, an assistant professor and principal investigator on the study, done in collaboration with the Walk Free Foundation, a group working to end forced labor, and funded by the Stichting de Chocolonely Foundation.

The child migrants arrive amid a vast wave of people entering from Burkina Faso and Mali. Ivory Coast is home to 1.3 million migrants from Burkina Faso and another 360,000 from Mali, according to the United Nations. Mali, Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast share an agreement on open borders.

Upon arriving in Ivory Coast’s cocoa-growing areas, child migrants are used to meet the demand on cocoa farms for arduous manual labor and stay year-round. There is land to be cleared, typically with machetes; sprayings of pesticide; and more machete work to gather and split open the cocoa pods. Finally, the work involves carrying sacks of cocoa that may weigh 100 pounds or more.

“Côte d’Ivoire has long been seen as a land of better opportunity in this part of the world,” McCoy, the industry spokesman, said. “That particular sort of form of trafficking speaks to a broader phenomenon that is not specific to cocoa, is not specific to Côte d’Ivoire but speaks of people seeking opportunity and that happens all over the world.”

“I came here to go to school,” says Abou Traore, 15, who arrived from Burkina Faso five years ago. “I haven’t been to school for five years now.”

Children leave the cocoa farm at the end of the workday.

Pisteurs, like this one here, are the middle men who collect bags of cocoa and deliver them to large commodities traders that supply the chocolate industry, such as Cargill.

‘We are hungry’

From the Ivorian economic capital of Abidjan, the village of Bonon is a five-hour drive along two-lane roads pocked with pond-sized potholes. From the outskirts of the village, footpaths lead into the surrounding forests, where farmers have created groves of cocoa trees.

In a patch of woods one day in March, another group of boys was at work with machetes. Each said he had come from Burkina Faso to work on Ivory Coast’s cocoa farms.

Like teen boys elsewhere, the boys near Bonon — Abou Ouedrago, 15; Karim Bakary, 16; and Aboudnamune Ouedrago, 13 — wore colorful branded sportswear. But they sleep in huts out in the woods, spend their days doing hard manual labor and don’t attend school or see their families. Karim’s yellow Adidas shirt was smeared with dirt. When one of the boys falls ill, they said they pool their money to go to the pharmacy.

“There is no money in Burkina. … We came here to be able to have some money to eat.”

Karim Bakary, child laborer

During a break in the typical March day — where the temperature ran into the 90s — the boys shared water scooped into a bucket from a nearby pond. It was milky white.

They said they came in search of a better life and are paid about 85 cents a day.

“There is no money in Burkina,” said Karim, who said he arrived here four years ago when he was 12. “We suffer a lot to get some money there. We came here to be able to have some money to eat.”

One time, he said proudly, he was able to send some money back home: $34. He said he would like to stay in Ivory Coast to make more money.

The most somber of the three was Aboudnamune. He wore a Spider-Man ball cap and rarely smiled. He said he arrived two years ago when he was 11. He answered questions haltingly, sometimes staring into the distance, and said he’d like to see his parents because “it’s been a while.”

“Yes, it’s a little bit hard,” he said of his life on the cocoa farms. “We are hungry, and we make just a small amount of money.”

A 2009 Tulane survey, based on interviews with 600 former migrant cocoa workers, offered a grim look at the economics that lead to child trafficking. Traffickers typically offer the children, who could be as young as 10, money or more specific incentives, such as bicycles, to take the bus to Ivory Coast. About half of those interviewed said they were not free to return home, and more than two-thirds said they experienced physical violence or threats. Most had been looking for work, and some said the money they were promised was never paid.

The man who was managing the boys for the owner of the farm, who declined to give his name, offered his perspective.

“Their parents abandoned them,” he said. “They come here to make a living.”

Then, apparently concerned about the attention the interview was drawing from passersby, he asked The Post’s journalists to leave the farm.

A boy holds his machete as he heads along a road to a cocoa farm.

‘A moral responsibility’

The most prominent, sustained public attention to the issue arose 18 years ago with reports from news organizations and the U.S. State Department that linked American chocolate to child slavery in West Africa.

“There is a moral responsibility . . . for us not to allow slavery, child slavery, in the 21st century,” Rep. Eliot L. Engel (D-N.Y.) said at the time.

Engel introduced legislation that would have created a federal labeling system to indicate whether child slaves had been used in growing and harvesting cocoa. It allotted $250,000 to the Food and Drug Administration to develop the labels.

The measure passed the House, but the industry was adamant that no government regulation was necessary.

“We don’t need legislation to deal with the problem,” Susan Smith, then a spokeswoman for the Chocolate Manufacturers Association, told a reporter at the time. “We are already acting.”

“Was there any chance of child labor being eradicated by 2005? No, never.”

Peter McAllister, who led the International Cocoa Initiative from 2003 to 2010

Engel, along with then-Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), opted to negotiate an agreement with the chocolate companies.

Now known as the Harkin-Engel Protocol, the deal kept federal regulators from policing the chocolate supply.

But the deal committed the chocolate companies to eradicate child labor from their supply chains and to develop and implement “standards of public certification,” which would indicate that cocoa products had been produced “without any of the worst forms of child labor.”

The top officials of Hershey, Mars, Nestlé USA and five other chocolate companies signed onto the deal. The signing companies had “primary responsibility” for eradicating child labor, lawmakers said, but the Ivorian government, labor organizations and a consumer group also pledged support.

The protocol also specified a deadline: July 2005.

Trucks loaded with cocoa bags are seen outside the Cargill facility in Abidjan.

Fishermen watch as a cargo ship carrying containers passes near Port Autonome d’Abidjan.

A chart showing Ivory Coast as producing the most cocoa in the world is displayed at the Choco-Story, Museum of Cocoa and Chocolate in Brussels.

Over the next few years, the industry approached the challenge with working groups, pilot programs and attempts to redefine its promise.

The industry created the International Cocoa Initiative, which was supposed to coordinate company efforts. The companies also formed a short-lived panel called the Verification Working Group. In West Africa, the industry supported pilot projects for monitoring child labor.

Even some insiders say the early efforts were destined to fall short.

Peter McAllister, who led the International Cocoa Initiative from 2003 to 2010, said the companies were “desperate” to avoid the legislation and promised more than they could deliver.

“Was there any chance of child labor being eradicated by 2005? No, never,” McAllister said. “They set themselves up for a bit of a disaster because of this magic date.”

“One executive told me at that point, ‘We would have signed a nuclear non-proliferation treaty,’ ” McAllister said.

Still, the industry gave the impression it was making progress. In February 2005, Smith, of the Chocolate Manufacturers Association, told an NPR interviewer that the deadline would be met.

“We have met every deadline established in the protocol agreement, and we’ll continue to do so,” she said. “We have large-scale tests of the monitoring system and the independent verification system in place. Those are going on now.”

But as Engel and others pointed out at the time, the companies were not close to meeting the deadline four months away. There were no consumer labels in the works; there was no clear verification system; the worst forms of child labor had not been eradicated.

Shortly after the deadline passed, the industry sought to reconstrue the meaning of a key clause in the agreement.

In 2007, industry officials argued that the promised “standards of public certification” did not mean, as some negotiators had thought, the creation of consumer labels indicating that a chocolate bar was free of child labor.

“Everyone in that room negotiating understood we were there to create a labeling requirement,” J. William Goold, Harkin’s lead negotiator on the deal, said in an interview for this story. “We were talking about consumer labels on chocolate. Anybody who thinks the language in Harkin-Engel means anything other than labeling for consumers is engaged in cynical self-delusion.”

Instead, the industry said, the agreement meant that the companies would produce statistics on West African “labor conditions” and “the levels” of child labor in West Africa.

In 2011, a decade after signing the deal, industry officials also suggested that it had committed the companies to an impossible task.

“The industry in fact does not know of any [certification] system that currently, or in the near term, can guarantee the absence of child labor, including trafficked labor, in the production of cocoa in West Africa,” according to a 2011 letter from an industry group representing Hershey, Mars, Nestlé and other companies, to researchers working on a study funded by the U.S. Labor Department.

“There was — and is — no roadmap to implement the Protocol,” the letter said. The “industry has in good faith carried out that agreement, while acknowledging several setbacks.”

A Rainforest Alliance certification logo and paintings that warn against child labor are displayed on a wall outside a cocoa cooperative facility near the city of Duakoua.

‘Certification isn’t enough’

As the industry struggled to come up with its own system for monitoring child labor, it increasingly turned to third parties to tackle the problem.

Three nonprofit groups — Fairtrade, Utz and Rainforest Alliance — provide labels to products that have been produced according to their ethical standards, which include a prohibition on child labor.

Over the past decade, the chocolate companies have pledged to buy increasing amounts of cocoa certified by one of these three groups. Mars reports buying about half of its cocoa from certified sources; Hershey reports 80 percent. In exchange for meeting the groups’ ethical standards, farmers are paid as much as 10 percent more for their cocoa.

Yet some of the companies acknowledge that such certifications have been inadequate to the child labor challenge. The farm inspections are so sporadic, and so easily evaded, that even some chocolate companies that have used the labels acknowledge they do not eradicate child labor.

Inspections for the labels typically are announced in advance and are required of fewer than 1 in 10 farms annually, according to the groups.

“Put simply, when the [certification] auditors came, the children were ushered from the fields and when interviewed, the farmers denied they were ever there,” according to a 2017 Nestlé report.

“Certification isn’t enough,” John Ament, Mars’s global vice president for cocoa, told Reuters in September.

Or, as an industry group representing Mars and Hershey put it, in a 2011 letter to researchers: “Given the absence of farm level monitoring, none of the three major ‘product certifiers’ have claimed to offer a guarantee with respect to labor practices.”

Representatives of the certifying groups acknowledge that their labels are imperfect tools for the eradication of child labor and that they are improving their methods.

“Child labor in the cocoa industry will continue to be a struggle as long as we continue to pay farmers a fraction of the cost of sustainable production. . . . Fairtrade isn’t a perfect solution,” said Bryan Lew, chief operating officer for Fairtrade America. But, he said, the higher prices for certified cocoa and the group’s efforts to organize farmer cooperatives are steps toward alleviating its root cause: poverty.

While most major chocolate companies seek to buy at least some “certified” cocoa, Hershey has pursued certification more than others.

Hershey “will source 100 percent certified cocoa for its global chocolate product lines by 2020 and accelerate its programs to help eliminate child labor in the cocoa regions of West Africa,” the company announced in a 2012 news release.

Leigh Horner, Hershey’s vice president of corporate communications and sustainability, said the company’s efforts are not reliant on the certifications alone. It views them instead “as one of many tools and strategies that need to be deployed. . . . Without the support of the local governments, these various efforts won’t work.”

Amadou Sawadogo, 18, from Burkina Faso, carries water to sprinkle on his freshly planted cocoa trees near the village of Blolequin. He has worked there for two years and has now started clearing a patch of forest for his own cocoa farm.

‘Severely inadequate’

One day this March, Amadou Sawadogo, 18, was preparing a patch of forest for a cocoa farm near the village of Blolequin, by the Liberian border.

He said he had been living in Burkina Faso and, when he was 16, came to Ivory Coast after “my father . . . asked [me] to come and look for money here.”

Like others here, he said it was common for Burkinabe children to come with traffickers to work in Ivory Coast and that the financial arrangements are well-known. There are about 30 young Burkinabe working around Blolequin, he said. Payments from the traffickers to parents depended on a child’s age. For a 15-year-old, he said, parents would be paid about $250. Once on the Ivorian farms, the boys make a little bit of money, typically less than a $1 per day, Sawadogo said.

None of this is legal under Ivorian law.

Ivory Coast signed the Harkin-Engel deal, too, and passed laws in 2010 and 2016 that define child labor and set penalties for its use. The Ivory Coast government committee handling child labor issues also said that it has taken other preventive measures: It built schools in rural areas and cracked down on people involved in child trafficking.

Child labor and child trafficking have flourished nonetheless because of the country’s inability to enforce the laws. As U.S. State Department officials noted in a 2018 report, the primary police anti-trafficking unit is based in the nation’s economic capital, Abidjan, several hours away from the cocoa-growing areas, and its budget is about $5,000 a year.

That amount, a State Department report says, is “severely inadequate.”

In a statement to The Post, Ivory Coast’s committee against child trafficking and child labor, said the $5,000 per year was not sufficient and that “the Ivorian government has to invest more in this area.” The country also has faced the eruption of on-and-off civil wars in 2002 and 2011.

Making matters more complex, some of the young migrant workers, legally the victims of child labor, say they’d like to stay. Though he had arrived only two years ago, Sawadogo said he was prepared to stay in Ivory Coast and had started clearing his own patch of forest for a cocoa farm. On his plot of land, Sawadogo had built a small shelter out of branches. It was big enough for one person to sleep in. He owned a couple of battered metal bowls and had some oil, which he’d use to fry bananas picked for lunch.

“I haven’t earned much money yet,” he said. “But here I’ve made a little money.”

The chocolate industry’s original promise called for the eradication of child labor in West African cocoa fields by 2005, next year’s goal calls only for its reduction by 70 percent.

A customer is served inside a Godiva store in Brussels.

Visitors at the Choco-Story, Museum of Cocoa and Chocolate, take photos of a large sculpture made of chocolate.

‘Nobody needs chocolate’

After missing the 2010 deadline, the industry established a less ambitious goal — to get a 70 percent reduction in child labor — and to do so by 2020. That goal, too, is unlikely to be met, the industry has indicated, and there is still no plan for consumer labels.

Over the years since striking the deal with the chocolate industry, Harkin and Engel have issued statements that sometimes supported the industry’s evolving approach and other times laid out their hopes for more improvement.

Engel, now chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, said policymakers have worked closely with the industry to make progress.

“The cocoa industry now makes serious investments in addressing child labor. We still have more work to do when it comes to this challenge,” he said.

Engel said the Foreign Affairs Committee is working on legislation to address child labor and supply chain issues and will likely hold a hearing later this year focused on the matter.

Harkin did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The problem, in part, according to some industry consultants, is that the companies have not done enough to fully investigate the depth of the problem.

The cocoa sector has sought “relatively little evidence relating to child slavery,” according to a report by Embode, a human rights agency, for Mondelez, a U.S. company that includes several chocolate brands, including Cadbury and Toblerone. There has been a “general lack . . . of sufficient attention” to the problem, the report stated.

In the last major survey to measure progress against the Harkin-Engel goals, a 2015 report for the U.S. Labor Department found that, based on interviews with about 12,000 people, the number of child laborers reported to have worked in West Africa the previous year had increased to 2.1 million from 1.8 million in the previous survey, completed in 2009.

McCoy, of the World Cocoa Foundation, said the results were “in many ways . . . disappointing,” especially given years of work on the issue. He did note some positive signs — of the Ivorian children working in cocoa, the percentage attending school had risen to 71 percent, up from 59 percent.

And, he noted, the companies have another program to combat child labor, one that now covers more than 200,000 West African farms.

The new system relies on hiring a local farmer to check other farms for child labor. If children are found working, the farmer is encouraged to send the children to school, and he or she is offered other assistance. The advantage, advocates say, is that the oversight comes from someone more like a social worker than a police officer.

In pilot programs, the new monitoring system reduced child labor by 30 percent over three years, but it’s still not clear how willing the companies are to extend the program to their entire cocoa supply. It can cost about $70 annually per farmer.

“If child labor is a priority, this is commercially sustainable,” said Nick Weatherill, executive director of the International Cocoa Initiative, which is developing the system.

Meanwhile, some experts note, what might be the most straightforward means of addressing child labor is scarcely mentioned: paying the farmers more for their cocoa. More money would give farmers enough to pay for their children’s school expenses; alleviating their poverty would make them less desperate.

Under the Fairtrade program, cocoa farmers receive an extra 10 percent or more of prices, but that is not enough to lift the typical Ivorian farmer out of poverty.

One small Dutch company, Tony’s Chocolonely, is paying an even bigger premium — about 40 percent more, in an attempt to provide a living wage. For a metric ton of cocoa beans that would normally fetch $1,300, Tony’s pays an extra $520, or about $1,820.

Asked how likely it might be for other companies to follow suit, Paul Schoenmakers, a Tony’s company executive, noted that many of the large chocolate brands may fear giving their competitors a price advantage by paying more. Schoenmakers said their premium cocoa price adds less than 10 percent to the cost of a typical chocolate bar.

“There’s no economic textbook or management book that thinks that [paying more] is a good idea,” he said.

The industry spokesman, McCoy, said he views the Tony’s Chocolonely effort as an experiment.

“Tony’s sources 7,000 tons of cocoa, which is a tiny amount. . . . How scalable is that approach?” McCoy said. “I think it’s an open question.”

But to Schoenmakers, it’s a simple matter. “Nobody needs chocolate,” he said. “It’s a gift to yourself or someone else. We think it’s absolute madness that for a gift that no one really needs, so many people suffer.”

Why The Washington Post is publishing children’s names and photos in this story

A reporter and photographer with The Washington Post spent 11 days in Ivory Coast reporting this story. Reporter Peter Whoriskey and photographer Salwan Georges traveled with a translator to three villages in the cocoa-growing region of the West African country: Bonon, Niambly and Blolequin. There, they interviewed 12 boys who gave their ages ranging from 13 to 18. The boys were working on farms harvesting cocoa, clearing brush with machetes and doing other work associated with cocoa production.

Before the interviews, Georges, through a translator, asked each boy if he agreed to be photographed and whether he consented to photographs that would identify him. Georges explained that such photos would circulate widely because The Post is available to millions of readers around the world and that may result in negative consequences for them. Most boys consented to having their faces photographed while several did not, so their photos were not published. All agreed to the use of their full names. Some of the boys interviewed remarked that they wanted their parents, who live in another country, to see their photos.

—

Design and development by Clare Ramirez. Photo editing by Bronwen Latimer. Map by Tim Meko. Copy editing by Sue Doyle.